- Home

- Heather Rose

The River Wife Page 10

The River Wife Read online

Page 10

I was eternal and the world was not. I was a fish and Wilson James was not.

One morning I stepped from the river to find Wilson James sitting in the rain. I took his hand and saw the scales that had formed there. I saw his feet. I saw the edges of his hair, his beautiful chest now patterned with scales beneath the fabric of his shirt.

The river carries the stories of air and mountain, of season and creature. Trees line the river and bend their words to it and the river fills with the music of birds, the nature of flight, the formation of clouds. The branches of trees arch out over the river and the river learns of longing and surrender and waiting. The creatures within the river are born and grow from egg and pupa and the river learns of belonging and kinship. Rocks lie on the bed of the river and whisper their old complaints of ice and crush and struggle and the river learns of strength and the weariness of age. The river flows and fish swim up it and the river learns of struggle and passion. And all creatures die and melt away into soil that is washed through by rain that travels down to the sea and is swept back up into the sky where it falls again as rain into the river. So the river learns of eternity and cycle and of coming home.

I understood that his life was simply one life, a thing that would be washed away, but it was his life, and I wanted him to have it yet.

‘It is time you came to the water,’ I said. ‘Tonight, when the sun sinks beyond the mountains, we will go together.’

‘What must I do?’

‘If it is as I suspect then it will be like this. You will feel the water take you and all of you will long to breathe beneath the river and you will slip into the river as easily as the grasshopper leaps or the bird takes wing. You will shed your human skin and find you have a swimming body with fins and a tail and these will guide you. The river will hold you and you will breathe as you have never breathed before. The colour of water and rock will meet you. You may be hungry and you will feed. The night will pass over and you will see its passing like a far world you can hardly remember, but you must remember. For when the daylight comes you must recall the warmth of the sun and the touch of earth beneath your feet and then you will step from the river and shed the skin of fish and walk again as a man.’

I took his hands. ‘Tonight you may be a fish but in the morning we will step onto the land again. And then we must leave for the mountains.’

‘I am sorry,’ he said.

‘For what are you sorry, Wilson James?’

‘I interrupted your world. I thought I had brought something good, but perhaps I was wrong. Perhaps it would have been better if I had not come here at all.’

‘I did not know you had any say in the coming.’

‘I longed for a way I could follow my son. I wanted to stay beside him forever, but I lost him and found myself here instead. If that has brought you harm or danger then I am sorry.’

‘We must go to the unknown lake,’ I said. ‘Tomorrow.’

He packed food and prepared but the day had a feeling of dying about it. The stories I wove as the rain continued were all of love lost and abandoned. I did not know if that night he would die as a fish, or if tomorrow we would begin a journey from which he might never return.

In the afternoon one last time did we lie together, one last time did our human bodies slip together, and so deep and sad and tender and raw was it that I felt as if my heart had broken into a hundred pieces and these I sewed in all the secret places of Wilson James. There where he had been lonely as a child, there where his God had hurt him, there where his son Eustace walked, there where the sound of the sea reminded him of loss, there where he had forgotten how to find a story that was his alone, there where he worried that death would take him young, there where he thought he was not worthy of love, there where he worried his life would be unremembered, there for when he was on the doorstep to death that he might feel no fear. One hundred places I found for love, and one hundred pieces of the fabric of my heart I sewed there to travel with him.

‘It has been good to love you, Wilson James,’ I whispered.

‘This is not the end,’ he said.

We stepped into the river and Wilson James slipped under the water and became a golden-bellied black fish with deep-circled eyes. Together we swam to the moonpool. I had wanted to stay with him one whole night. And he had wanted to find a story. He had come to the river and now he was part of it. I showed him the creatures which live on the river bottom and underneath the river rocks and are good to eat. We swam together through the river’s currents and I leapt above the surface for the flies that hovered in a rise there near the waterfall. Wilson James leapt with me, a little leap at first, and then higher. All night he shimmered beside me in the moonpool, and deep and quiet was the night. Above the river’s surface stars spun across the sky chased by the moon, and rain fell in mist about the forest, but in the moonpool I was aware only of the shift of him and the watch of his gaze beside me. In the morning I found the face of his fish-self in the brightening day. I swam with him to the water’s edge and stepped from the water. But Wilson James did not step onto the river’s edge. He flipped and turned but he stayed as a fish.

I stepped back into the water and coaxed him to remember himself as a man.

‘You must try, my love. Please try. You are a man. You love this earth. You are a writer. You make bread. You like to feel the sun on your face.

You cannot do without coffee in the morning. Oh, please, my love, come back to me. Please step from the river. You are Wilson James and you need to remember. Please.’

I implored the fish before me to become the man I loved. But already he was swimming away as if he had quite forgotten me and the riverbank and the place where we had lived as a man and a woman. I swam after him but he slipped fast downstream and soon we were both in the great lake, and from there I lost any trace of him. All day I swam, ignoring my duties to the river, and all night too I searched for him. Day after day while rain deepened the lake and mist held close the sounds of birds calling and fish jumping, I searched for him. I did not know if he would ever find his way back to me, nor to the man he had once been. The world he had brought to me was silent. It was as if he had never been. I was beyond songs I knew or any stories I had heard.

It is said that at dawn there is a moment women know that is neither day nor night, and there a doorway may open. It is known by young queens seeking victory in battle, by fallen brides seeking the halls of their ancestors, by crones waiting for the visit of death, by mothers waiting for the breath of a dying child to return. It is said that in the moment of dawn it is possible to glimpse the world as a brief flicker of nothing more than light and all of us upon it as creatures of light, and there it is possible to ask for anything and have your wish granted.

I did not know if I could find the oldest ones. I did not know if they would help, but I knew I must ask. Perhaps they would laugh at the foolishness of a river wife taking a man into her world. Perhaps they would turn away and let Wilson James die as a fish. Perhaps they would take my life for his.

I did not know the way to reach them. All I could do was hope that my father had been right. That the stories were right. And that the unknown lake was a doorway to the Lake of Time.

I could not leave my love in the river. I imagined what a mighty catch he would be to the fishermen downriver, the fish whose scales were gold against his black skin.

‘What fish is this?’ they would wonder.

‘One of the big fish from further upriver.’

And they would not eat him but mount him on a wall, as Father had told me. And my love would live no longer.

And so at nightfall I began my journey to the mountains and the unknown lake alone, swimming up and up, drawn higher and higher, my fish body strong against the flow of water that sought to wash me away. Above the highest lake I chose the deepest of the rivers that flowed from the mountains, and I swam through the crevasses and up waterfalls new with snowmelt. But I knew soon enough I must leave the river and

make my way as a human high into the mountain peaks, and there was no easy way to traverse the rugged slopes that lay above me.

The story of the river wives was mine and mine alone, and I wished I had told it to Wilson James when I had the chance. But there were stories of older creatures, who were here before the river wives arrived. They lived far from light and it was said they cared not for people. These oldest ones governed not stories but time, and time was their river. It was they who set the span of years for man and woman, for tree and flower, for beast and bird. When time was sought, more or less, time beyond what the day and night could give, time for finishing or starting, for beginning or ending, for chance or luck or even death, it was to these oldest ones that all beings turned.

As light touched the sky I stepped from the shallow bed of the river and took my woman’s form, breathing in the pale air, my feet deep in the powder of snow. But it was not from my father I sought guidance as I looked to the far peaks above me that morning.

‘Mother,’ I said, ‘you made this journey of love between a river wife and a human. Did you survive it? Or did you give your life so my father might live on? I would do anything to save this man. Help me. Please help me. I do not know the way.’

Perhaps it was the moment of dawn that women know, or perhaps my mother had waited all this time to hear my voice, for it seemed that a pathway became clear to me through the snow and I began to climb. I felt my body ache as I went further and further from the river. The snow hid many deep holes and gaps, and the rocks were harsh beneath. By halfway through the day I was tired beyond imagination. My mouth had dried, my skin burned for water and my ears called for the river. The path became steeper but still I climbed. I was dizzy at the view across mountains crumpled by age and laden with snow. Far away below me in one valley I could see the deep green of the forest.

Had Wilson James remembered himself and stepped from the lake? Was he right now returning to the river? If I did not find the unknown lake, if it did not take me to the Lake of Time, would I die here tonight so far from water? And if I died, what would become of him?

My arms shook as I pulled myself up and my legs trembled as I demanded of them another step and another and another. The wind worked at my skin, chilling my hands until it was hard to open them to grasp another ledge, another surface that might lead me further up and up. Louder became my body’s fear at leaving the river. I began to imagine the sound of water trickling, running in behind the rockface, but I saw no glimpse of it. I heard water rushing as if nearby a waterfall was flowing. But when I scrambled to find it there was nothing but a great chasm that fell down, so far down, to the valley floor. I had never known the world was so high, and cold. No matter how I tried to summon the clothing I needed to protect me, nothing kept the ice from forming on my skin, crusting my eyelashes and cracking my lips. Night was slipping over the world in a purple blanket and still I had no idea how far I must climb, nor if the path I followed would lead me to the lake that had no river flowing from it.

I pulled myself over a long sharp ridge as sunset slipped off the peak, carrying from the land the last of the colour, and there below me, cradled in a deep bowl of carved stone, was a great expanse of ice. I slipped down the rocky slope and found myself on a flat grey edge that rimmed the ice. I could smell the water beneath it. I tried to pull and stamp at the edges so that the ice would break and I might slip into the water but it was thick and strong and did not move. I grasped a sharp sliver of rock and beat at the ice with it but it merely grazed the frozen surface.

I stepped onto the ice feeling for movement, for a section thin enough for me to crack open and slip through. My legs were so weary they could hardly lift my feet. Further and further across the ice I walked until I was surely in the centre of the lake, but the ice held fast. And there I lay down. I lay down and did not have the energy even for tears. The stars were emerging larger than I had ever seen them. No trees shaped the sky or brushed against their light. They were so close I might have reached out and balanced each one upon my fingertip.

‘I am a river wife,’ I said to the stars. ‘You know me. You know my journey. I must find the way to the oldest ones but I have no key. I have nothing. Nothing.’

My breath was leaving me now. I felt strangely light. I anguished that I had not thought to bring any of the tools Wilson James had packed. The knife he wore at his belt. The small axe. Turning onto my side, still holding the shard of grey stone I had used on the frozen edge, I drew in the ice a flowing line. A line of water. And beside it I drew another. The symbol of a river wife. The symbol all river wives knew, that I had drawn on the skin of Wilson James in red jam, the flow of water that has no end.

‘I am a river wife,’ I said, though I had little voice to speak. ‘I am a river wife,’ I said again, and I dropped the stone and laid my hand upon the symbol. ‘I am a river wife.’ And the ice disappeared. My hand touched water. The hole widened, the ice collapsed around me, and I slipped into the darkness of the lake and the stars went out.

Down I fell. So intense was the blackness I could not see my limbs. Sometimes I felt as a stone must feel falling fast through water, and other times I was sure I was urging myself deeper and deeper into darkness.

When does love become more than love? When does it go beyond a simple explanation of someone familiar and beloved to something wondrous? When does it become something worth dying for? I had watched as we wove our lives together and then I had stopped watching and lived in the threads of our existence and it was more than I had expected. There was a song singing but I did not sing it. There was a season but it had no name. There was a sense of knowing that surprised me, as if he was someone familiar who I had somehow forgotten and was now rediscovering. I do not know when I slipped out of being myself entirely and took up occupying some place where we both were. Longing was fulfilled, sadness relinquished, joy claimed. There is something that lives beyond the shores of love and it is its own lake. As I fell I considered that perhaps the lake that love can lead us to and the Lake of Time were not so different.

Still I fell, until at last I found I was no longer falling and the great force that had swept me downwards no longer held me. I broke the surface and breathed in darkness. I swam towards a luminous shore and stepped from the water. Somewhere above me I was sure it was nightfall, though here I was a woman.

A sound came to me of voices singing. I walked towards the sound along the shore of that strange lake and passed glowing rocks that had grown up out of the ground and others that had grown down from far above and these stones were white and luminous against a deep blackness.

I entered a cavern more vast than the tallest tree and wider than the great lake. Spirals and cones of stone twisted and dripped, and every surface sparkled as if moonlight glowed here, so far underground. All about was the dripping and running of water. I knew I was looking at the Lake of Time and I wondered how old I had grown on my journey here. My hands looked no different, nor did my skin, but I knew Time would visit me at any moment and I was not without fear.

Standing at the edge of the lake, dressed in a gown of silver that moved and shimmered, was a woman. The singing ceased and it was her voice, not the voice of many, that had echoed down the passageways that led here. She said without turning to face me, ‘Human love has visited you and that is the strangest visitor of all. So full of wonder and hope, and then so binding with all its demands.’

‘Yes,’ I whispered.

‘Would you take it back, any of it?’

‘No, but I would not have him lost forever.’

‘And what would you give to save him?’

‘I do not know—everything, I think.’

‘What is yours and yours alone to give?’

Still she had not turned her face to me.

‘I could give my voice. I heard that another of us . . .’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘you could give the voice that sings the songs of the river, but they will expect far more than that.’

/>

‘They?’

‘Do you know me even a little bit?’ she asked as she turned her face to mine, and the face that looked at me, the translucent skin, the green eyes, the dark falling hair, it was my face.

‘Come, my daughter, sit with me.’

The world moved so slowly that I could not lift my feet to walk to her, but still I found myself beside her.

‘Do not be afraid,’ she said. ‘I am your mother. I am not one of them. Like you, I am a visitor here.’

‘How can you be here?’

Her face was grave but her eyes were warm and filled with tears. ‘I am saddened to see you here in this place where none but those with everything to lose must come, yet now that you are here, now that you have found your way as I found my way before you, it brings me more joy than you can know to gaze upon you. So long have I waited for this moment.’

‘You have been here all this time? Why did you not come home?’

‘I could not.’

My mother stood before me. The woman whose songs and stories lived on in me. The woman who had cared for the river and lived by the river, the woman who had taken my father for a husband and started this whole cycle of human and not that had bound me as sure as the sun and moon bound me. I wanted to turn away from her and I wanted to curl up with my head on her lap and cry. Why was she here? What had made her stay here and not come home? I saw Father beside me on the riverbank. Father, who lived so much longer than any man had lived. Father, who had never left the river because he waited all that time for her to return.

‘For Father? Did you do this so he might not die?’

‘Does he live still?’

‘Yes, he is standing by the river above the moonpool and he wears the long robes of a myrtle beech and many birds live in his branches.’

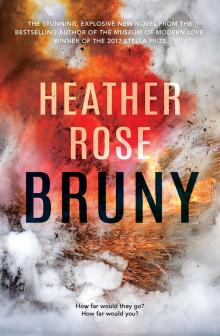

Bruny

Bruny The River Wife

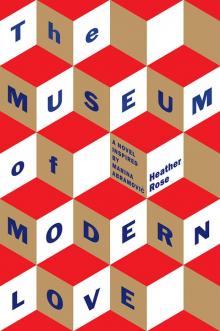

The River Wife The Museum of Modern Love

The Museum of Modern Love