- Home

- Heather Rose

Bruny Page 3

Bruny Read online

Page 3

‘No,’ she said. ‘I hear it’s heavy going.’

‘The loss of diversity is killing us … In a nutshell, fifty per cent of what was once here in terms of individual species is gone. It heralds the end of human life as we know it.’

‘Cheery,’ she said. ‘Just like him.’

I looked at her.

‘He takes himself very seriously,’ she said.

‘What’s he doing in Tasmania?’

‘What everyone else is doing. Escaping. Funny how they don’t though. When something like this comes up, it’s as if they can’t wait to reclaim some missing part of themselves.’

‘Their stress,’ I said.

And we chuckled.

‘You said yes to him,’ Max said, and I knew she meant our brother, John.

‘I also said yes to coming home for Dad,’ I said. ‘And you.’

‘And Mother,’ added Max.

‘Yes,’ I said, and we exchanged one of our looks.

Here was the rub. It was always the rub. Max was our older sister but JC was my twin, our little brother. Technically Max is our half-sister, because she was born the year before our parents met. Max’s father had been much older and he’d died in awkward circumstances when our mother was just twenty-two. Our father, Angus Coleman, Labor MP in the Tasmanian parliament, fell in love with the beautiful young widow and the rest is us. The media liked to drag it out from time to time, referring to Max’s ‘half-sister’ status to the premier, but for me it has never been an issue. Not for our father either. I’m never sure if JC feels the same. Let’s face it, politically Max is a major thorn in JC’s side. At moments like this, it can get a little murky for any number of reasons, families being what they are.

Max navigated the traffic as we entered the city and passed the docks where the fishing boats moored and the fishmongers plied their daily wares. The whole place was looking a little more modern. New hotels, more people. But the same deep blue river and architectural mistakes.

Both of us were looking older. Max’s lines had settled around her mouth and neck. Her short pale hair, pink suit and lemon blouse were camera ready. Max has the vigour of a Stepford wife, yet I could feel her weariness too. Maybe it’s just that we’re women of a certain age, had our fill of looking after people and doing their bidding. I’ve seen Max’s breed of weariness in so many political figures. Good people run by their desire for public service but worn down by it all. The being on call, the critics, the staff, the volunteers, the voters, the media, the election cycle. The stories that are only half true, the back-stabbing, the compromise. The brain that never stops churning. People trading their values for a little bit of legislation in the hope it will change the world. And, if they’re women, everything it takes on top of that.

‘Have you heard the latest plan?’ Max asked.

‘For Mother?’

Max shook her head and smiled. ‘No, for the bridge.’

‘Tell me,’ I said.

‘They passed new foreign labour laws in federal parliament this week. It’s finally happening. We’re going to have three hundred Chinese construction workers on the bridge.’

‘I heard,’ I said.

‘So he can cut the ribbon on March fourth and it’s on the front page of every paper election morning,’ said Max. ‘Bar another bomb, I don’t think anyone can stop the bridge. It’s too big an investment.’

‘So I’m not really needed?’ I asked.

Max made a face. ‘Probably not. It was a good thought. Bring in an outsider who’s not really an outsider. He’ll cop more flack than you over the nepotism thing. Of course, I’ve put out a statement saying I think we must be proactive and that I support your appointment wholeheartedly. The community needs solidarity right now. People are really shaken up. The bomb was a dark turn no-one anticipated.’

‘What are the polls saying?’ I asked.

‘There’s a new one in the paper today. He’s on thirty-eight per cent as preferred leader.’

‘And the Greens?’

‘Their leader is Amy O’Dwyer,’ she said, one hand momentarily lifting off the steering wheel and rubbing her forehead. ‘I’m sure that’s in your briefing notes. She’s a Cygnet girl. Incredibly beautiful. Looks like a young Penelope Cruz. Smart, too. The Greens were running at twenty-one per cent, but since the bomb they’ve dropped a couple of points. Still, young Amy is running at thirty-five per cent as preferred leader. The public like her.’

‘Ouch. JC will be hating that.’

‘I’m hating that,’ said Max.

I quickly did the calculation. If JC was on thirty-eight per cent and the Greens leader was at thirty-five, that meant Max was on twenty-six per cent or less as preferred premier. In our family, statistics have always been personal. In New York, I rarely told people that my brother and sister went up against one another in elections. Even for New Yorkers, who are almost impossible to surprise, this raised eyebrows.

‘So what did we pull you out of?’ asked Max.

I thought back to the Yazidi women, the body in the cage, the air strike.

‘The Middle East,’ I said to Max.

‘You okay?’ she asked.

‘Sure,’ I said.

There are many things I do not tell my family. Things I can’t explain.

Beyond the city we took the road past the university and deep into the affluent riverside suburb of Sandy Bay. The tinted windows of the car did nothing to block out the visual nightmare that was the steep urban sprawl of Churchill Avenue. You could be forgiven for thinking some great monster simply spewed the rendered houses with their double garages, mirrored-glass windows and tiled balconies out onto the hillside at quarter-acre intervals. There were slums in Rio that, but for a coat of Dulux and a few pool fences, would entirely resemble Hobart’s second-highest income-per-household suburb.

Max pulled into a driveway barred with high white gates. She leaned out and pushed the buzzer. A brief exchange took place between her and a distant female voice. The gates opened onto a paved driveway lined with agapanthus and white standard roses leading up the hillside.

‘So this is how he lives now?’ I asked.

‘A man of the people,’ Max said, then her voice became subdued. ‘Ace …’

‘Yes?’ I said.

‘I know it’s not what you’re here for, but there’s something really fishy about the bridge. Too many unanswered questions. In a way, it’s not surprising someone tried to blow it up.’

I waited.

‘Nothing about it adds up for anyone other than certain people with their heads in the sand.’ She gazed at JC’s ahead.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘And you’re right: I’m not here for that. I’m here to get everyone settled down. No more terrorists.’

‘I understand that,’ said Max. ‘You’re here to smooth things over for him. Buy him time so that on the fifth of March he wins office again—I get it. But you and I need to talk, sooner rather than later.’

We were at the top of the driveway. Max killed the engine.

‘How about an early-morning walk?’ I suggested.

‘Sounds good,’ said Max. ‘Let’s give you a few days to settle in first, though. Let you hear his side of things.’

I nodded. ‘Maybe Monday morning?’

‘The old Regatta Pavilion, six am?’

‘Okay. It’s still there?’

‘It is,’ she said, smiling, and I smiled too. It was an old haunt. Scene of many an act of misspent youth. Or, possibly, well-spent youth considering how serious our lives had become since those days.

We got out of the car and proceeded to unload my bags from the trunk.

‘If you’re on his side, Ace,’ said Max, ‘I know you can’t be on mine. At least, not so he can tell. Nothing new in that! By the way, they’re having a lunch for you on Sunday. To welcome you home.’

‘And you’re not coming?’

‘Course I am—wouldn’t miss it,’ Max said, jumping back into the car and start

ing the engine. She wound down the window and called, ‘Stephanie will pick up Mother and I’ll bring Dad.’ ‘Astrid!’ came a voice, and there at the front door was Stephanie, JC’s wife, in jeans and a striped blue shirt, looking every bit the ageless blonde Sandy Bay wife. Stephanie, who had arrived in our lives like Araldite about fifteen years ago and insisted everyone stick together. She and Max waved to one another as Max departed. Behind her, two girls emerged from the house.

‘Girls, it’s Aunty Astrid!’ said Stephanie. ‘She’s finally home.’ Then we were all embracing.

CHAPTER THREE

Even unfinished, bombed and listing to one side, the Bruny Bridge was still an extraordinary piece of design. It towered over the channel, dwarfing the hills and dominating the sky. It was a curved six-lane single span, far bigger than the Derwent Bridge that crossed the river to Hobart. Hobart was a city of one hundred and twenty thousand people. Yet this huge bridge—longer, higher, wider—was taking people to a remote island with a population of only six hundred.

Living in Manhattan, I’ve learned a distinct appreciation for bridges. The UN is on the East River. For years I crossed the Manhattan or the Brooklyn Bridge, cabbing back and forth, or taking the subway through the tunnel to Prospect Heights, until we moved to the East Village, after Ben and I separated. Such an inadequate word—separation—for that chaos, but if you’ve been through it, you’ll understand. I’ve seen impressive bridges in my travels. Seen quite a few blown up too. The former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Enough said. But this bridge was truly audacious. Perhaps Washington Roebling felt the same when he envisioned the Brooklyn Bridge back in 1869. Though let me say, every time I look at the Brooklyn Bridge, I see the largely unrecognised Emily Roebling, his wife, who got the thing finished after Washington got the bends and was bedridden. She was the first female field engineer and she learned it all from scratch. Same thing with Canberra, Australia’s capital city. The architect mentioned is always Walter Burley Griffin. He had the lake at the heart of the city named after him. But it was his wife, Marion, who drew up the plans. Don’t get me started.

The Bruny Bridge had been designed by the winners of an international design competition—Santiago Calatrava and Satoshi Kashima—legends of bridge design. The result was spectacular, even in its injured state. Considering it was costing two billion dollars, I supposed it ought to be.

Standing beside me, observing the damaged bridge, was Frank Pringle. Frank was JC’s chief of staff and number-one adviser. He and I had just come from a meeting on the rebuild program with my brother and a room full of people in the premier’s boardroom back in Hobart, a twenty-minute drive upriver. I had just witnessed my brother in action as premier of Tasmania for the first time. He’d been premier for almost eight years but, watching him, it was still a little unbelievable.

He’d introduced me very formally as Dr Astrid Coleman from the UN, proud to have this connection even though I wasn’t here under that brand. I was here as an independent consultant, though ‘independent’ had taken a battering in the media, given my family connections. JC hadn’t called me Astrid in decades. I was always Ace, since we were teenagers. Because they were my initials, and because I was good at poker and Cheat. Any game where I have to hide the truth, that’s always been my specialty.

Across from the executive building, where we were meeting, was Parliament House. I felt as if I had grown up in those green-carpeted corridors, visiting my father’s office, sitting in the gallery while he debated gambling licences, forestry licences, hydro dams and new schools. He was a politician for forty years, our father. Minister of this and minister of that, but never premier or even deputy premier. Now his son was premier, but for the other side of politics. None of us had quite forgiven JC for that betrayal of Dad’s legacy.

The meeting in JC’s boardroom had not been easy. The forensics on the bridge were still incomplete. Divers would be down there for days yet, but it was evident what was required. Repair the bombed tower. Repair and re-tension the damaged vertical cables. Rebuild the road sections. Sounded easy in principle, but on a massive structure nothing was simple. Still JC had been adamant.

‘Whatever it takes, this bridge has to be open, and the traffic flowing, on March the fourth. That’s why you’ll have an extra three hundred skilled workers and the budget to get it done,’ he’d said. JC’s an inch taller than me. I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s two-hundred and fifty pounds now, and it’s not muscle. I’ve lost track of metric living in the US for so long. He’s a big man.

The chief engineer was also tall, but lean with long grey hair that made him look unsettlingly like Gandalf. He was loath to commit to a new schedule when the damage was still being assessed. Mick Feltham, the bridge director, had been equally adamant. Escalating the schedule spelled trouble. More than trouble, it spelled death. He reminded us that twenty-six thousand people had died to build the Panama Canal. Under a fanatical director, they were crushed in tunnels, drowned in concrete and died in the thousands from yellow fever, just to get the canal finished so the bridge director could collect an enormous personal bonus. Mick Feltham was not that man. He wasn’t prepared to have a death on his hands because of an unrealistic schedule. But the word ‘bonus’ had hung in the air.

I could see JC weighing up what kind of a bonus it would take for Mick Feltham to get the job done. Then he placated the man. This was how he got his nickname—not because J and C were his initials, but because he can be convincing in an almost biblical way, even when you know you’re being worked over. JC has that most dangerous attribute: charisma. People warm to him. People trust him.

‘Nobody wants a death, Mick,’ JC said. ‘I don’t want a death on my hands. None of us do. We’re not expecting you to risk lives. But I trust you to solve this.’ He’d paused and smiled at Mick Feltham. ‘You’ve done this kind of thing before, Mick. That’s why I knew you were the man for the job. It’s been a long few years. Your family’s probably worn out by it too. But it’s so close to completion. Look at it this way—if we don’t have the bridge finished by March fourth, we let the terrorists win. We let terrorists win the world over. You don’t want that. I don’t want that. Our families don’t want that. None of us want to live in fear. This bridge is a symbol, Mick. You know that. It’s a symbol of hope. It’s a big, beautiful, literal and metaphorical bridge between old Tasmania and new Tasmania. A new vision for Tasmania. Real prosperity. And you’re the man we’ve trusted to deliver that for us.’

The federal minister, flown in that morning, looked like he might shed a crocodile tear. His name was Aiden Abbott, but on social media he was known as Aid-n-Abet and he was the Minister for National Protection. His portfolio stretched from border protection to internal affairs and he was enormously powerful. With his dark suit and balding head, he might have come straight from the set of The Sopranos.

‘Anything you want to add, Minister?’ JC asked.

‘The prime minister sends a personal directive: Make it happen,’ said Aid-n-Abet. ‘So, Mick, I’m here to make sure you have everything you need in order to make it happen. We’re giving you the workers. We’re getting you the steel. We’ve called in a world-class conflict resolution specialist to settle the protestors.’ Here he nodded to me. ‘We’re doing all we can to assist you.’

I could see that whatever bonus Mick Feltham was going to ask for, the feds would pay. I wondered when that would occur to Feltham.

JC turned back to Gandalf and asked him again if it could be done. The chief engineer looked sadly at Feltham, then at JC, and said that, as he’d said before, more investigation was needed. They’d only had a week and they were still assessing the damage. The suspension cable had been damaged back at the anchor point, torched, and that was going to present some problems. But it was the footings deep in the seabed that were the real issue. Until he knew repair was possible, he couldn’t be sure.

‘If it can be repaired, are we good to go?’ JC asked.

The chief engineer took

a breath and said, ‘Yes, Premier,’ guessing correctly at last that this was all he was really there to say.

The federal minister nodded. He applauded everyone’s commitment, slapped Mick Feltham on the shoulder and told him he was a good man, shook hands with the chief engineer and said he had every faith in him, and then Aid-n-Abet was gone back to Canberra via a fifteen-hundred-dollar-a-head fundraising lunch with JC and party donors at the famous art gallery just outside Hobart, while Frank and I came down to the site.

It was a breathtaking view. We had stopped at this vantage point on the headland above Tinderbox so Frank could show me the bridge. In Hobart, upriver, the Derwent was probably about the same width as the Hudson between Manhattan and New Jersey, but here at the mouth of the river it was four times as wide. Blue-forested hills stretched away on the far shore towards the Tasman Peninsula, one-time convict headquarters of the British government. The bleakest, coldest, most savage of all the British penal settlements. When we were growing up, the idea of a convict in a family’s past was scandalous, but now it had become fashionable to claim a thief, a forger, a con man.

Between Bruny and the Tasman Peninsula was Storm Bay, a wild, exposed bit of sea that can be as benign as a lizard in the sun and then as fierce as a she-wolf protecting her cubs. Beyond the broken bridge was the northern tip of Bruny, and the village of Dennes Point. North Bruny has always been a far more remote destination than South Bruny, although it didn’t start out that way. The first ferry service across the channel ran between Tinderbox and Dennes Point back in the 1800s. Later the service moved down the channel to Kettering, with its mirror-calm harbour nestled under deep green hills.

Dennes Point lacked sufficient rainfall, a pub and a service station—the staples of any town—to draw the hundreds of shack owners who had built their weatherboard and fibro cottages on South Bruny, where there was regular rainfall, shops, cafes and an essential pub. There had been a shop at Dennes Point when we were kids, but it had closed long ago.

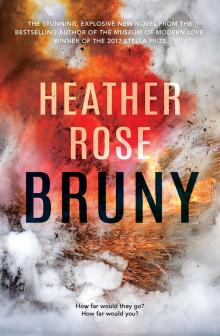

Bruny

Bruny The River Wife

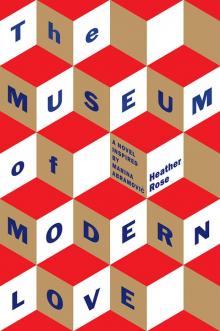

The River Wife The Museum of Modern Love

The Museum of Modern Love